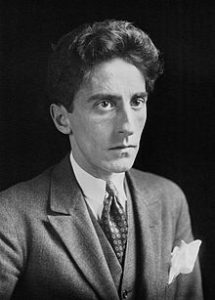

A great name in the dance world and a great master for those who had the privilege of navigating through their art under his benevolent guidance…

An inspired choreographer and a consummate artist.

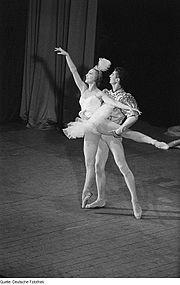

A performer who was transfigured by the figures that he personified.

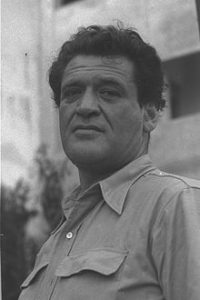

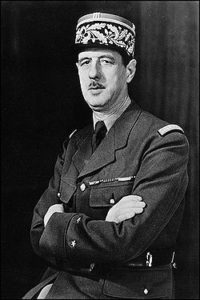

When he played Napoleon, he was Napoleon. When he played a pharaoh, he was a pharaoh, and in Icarus he burned his wings in the sun and symbolically died on the earth, consumed by the ambition to exceed human potential… In this connection, we could speak of his mystical side, which might go unnoticed by those who knew him only superficially, for in these moments of transfiguration, he was overwhelmed by the fact of having another, impalpable inner life. At such times he lived inwardly, detached from the world. During a tour in Egypt, we were both inside a pyramid and contemplating the room that had contained the sarcophagus of a pharaoh. Since Lifar was not saying anything, apparently lost in the mystery of the place, I broke the silence and said: “Your place is here, master”. He looked at me and replied: “”Do you think so, Labis, do you think so?” At that moment, he was the pharaoh. We see a person according to our own criteria and memories.

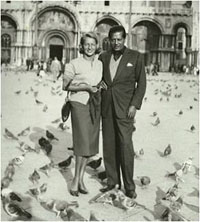

Personally, I have the memory of a charming, kind and good-natured person, sometimes touchingly so. He had a poetic way of talking about the dance, like the feel of the tip of a dancer’s toe on the ground. We talk of classical ballet, a universal art… he attached a great deal of importance to the rise of this French invention called classical ballet, which he emphatically sublimated.

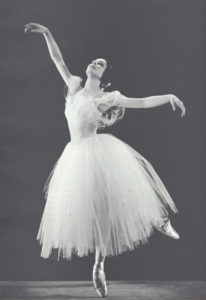

One day, he told me that the “Italians and Russians have interesting temperaments for the dance [he meant the extremes that characterise great sensitivity and a passionate, at times, uncontrollable expression], but you, the French, you have something that is rare and that no one else has: that is, a sense of measure”. He was obviously not talking about music, but of the precise gesture, where it has to be in order to maintain balance and the sense of movement. He had a genius for never forgetting himself when he wrote a dedication. He once dedicated a superb photograph from his Gisèle of the 1930s “To Attilo Labis, a magnificent Albert Loïs in the Lifarian tradition”. It was a generous compliment for me, but also for himself…

Lifar was scientist of the stage, with a perfect knowledge of the artists who had to be in such or such a role. And if he was upset when the dancers had botched their entrance or lacked musical feeling, he would say—and this was the supreme insult—”Go dance in Angoulême!” In his eyes, Angoulême was the worst of all provinces, yet, one day several years later, during a trip of the Paris Opera, he performed in Angoulême. Lifar stands for developing instinct before thought, aesthetics before placement, combined with knowledge and the mastery of his art.