Serge, Evguenia, Vassili, Leonid

His childhood

He had dreamed of becoming a soldier and marching in step, but he became a dancer with aerial instead of martial steps. Serge Lifar says as much in his autobiography.1 It was in August 1913, he was eight years old, as he clearly remembered: “I put on a little uniform and wore a cap with the insignia of the Imperial College of Alexander in Kiev. But my dream uniform was a completely different one. It had red epaulettes, bore the initials I.K. and a gold-trimmed collar: the uniform of the First Corps of Cadets. I dreamt of being a soldier, especially in the cavalry: tall, thin and handsome, riding on a horse as white as snow, I galloped bravely at the head of a squadron that I was leading into battle”.

His father

Born on 2 April 1905, in Kiev, the Ukrainian capital on the Dnieper, Serge Lifar spent a happy childhood, spoiled by his bourgeois family. His grandfather on his mother’s side had been a cattle breeder, a descendant of the great landowners who extracted salt from the Caspian Sea. As we know, salt preserves—indeed, he lived to be over a hundred. A large garden full of flowers, kittens purring, such was the setting of his childhood: “When I misbehaved, the hardest punishment that my parents could inflict on me was to shut the little cat in the kitchen for the evening”.

His father, Michael Lifar, was a functionary. His older brother by one year, Vassili (Basil in English), was to become a painter and his younger brother by one year, Leonid, a fighter pilot. This trio was completed by an older sister, Eugenia. She was also to establish herself in Paris and make a career in gastronomy. Serge Lifar kept a loving image of his father: “He was gentle and kind. Elegance and order were the things he liked the most. He surrounded himself with nice furniture and precious bibelots. He needed a harmonious atmosphere. He never raised his voice, but spoke to us like to one of his friends. He knew how to respect childhood. I was his favourite”.

His mother

For his mother, Sophie Lifar, he had a boundless affection: “I had a veritable adoration for her that manifested itself in outbursts of enthusiasm and deep despair. I remember when she went for a month and a half in Crimea with the entire household, leaving me behind in Kiev with a nanny for some reason. I must have been about four. That the others left did not matter much, but I could not believe that my mother would abandon me and I wept bitter tears, something that rarely happened. This trip to Crimea cast a dark shadow on my past”.

Radio Lausanne, Glion, 13.08.1983 : Son enfance a-t-elle été plutôt riche ou plutôt pauvre ?

The Great War

When war broke out in 1914, Serge Lifar thought that he would enlist in the Russian army, in which twelve of his uncles were already serving! Kiev became the converging point for countless armies: “I spent my time dreaming about the war and forging plans of escape to go to the mysterious and so very appealing front”.

The young Serge was a good student and sang in the choir of the Cathedral of St. Sophia in Kiev: “I sang at every Mass. My parents were proud of my musical success, but they would not let me go to the theatre. In their eyes, it was the symbol of disorder and the temptations that could lead a precocious spectator to perdition”.

With the October Revolution of 1917, Lenin enjoined the soldiers to abandon the front and incited the people to rebel: “Steal what has been stolen!” The result was panic and anarchy. Soldiers deserted, killing their officers. A merciless class struggle began with the aim of eliminating the bourgeois. The Bolsheviks took Kiev, which was subsequently captured by the Germans, who gave the land back to the peasants under the threat of their bayonettes. But life eventually went on as usual. There came a period of Ukrainisation: “Official documents had to be written in an artificial language that people did not understand”. The young Lifar was shocked by the horrors of war: “The Germans set up machine guns in front of the rebellious villages and killed everything that

moved. The people were locked up in their houses and they were set afire. The few Communists left in the countryside took advantage of this to incite the mujiks to revolt, and they avenged the burnt houses by capturing German soldiers and boiling them in huge cauldrons”.

After having served in the White Army, Serge Lifar was recruited in the Red Army. At the age of sixteen, he became an officer and was given a new uniform, a large revolver and the command of a few dozen “young rowdies”. The Soviets made it a point to take the still malleable adolescents away from their bourgeois or peasant parents in order to turn them into “good” Communists. They abolished private property and all the houses were declared State property, administrated by a committee of tenants. Businesses were closed and the government distributed rations. As he relates in Ma Vie, published in Paris in 1965, Lifar estimated that, of his 200 young comrades, only three survived: himself, his brother Basil, and Cerna, who went on to create a dance shoe business under his own name in Paris.

Bronislava Nijinska in “Petrouchka” 1911

Initiation to the ballet

In 1920, through a schoolmate, Serge Lifar discovered the ballet of Bronislava Nijinska, the sister of the famous Russian dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky. It was a revelation: “I withdrew to a corner of the room, my heart beating wildly. I experienced an enthusiasm that I had never felt before. Madame Nijinska’s pupils were dancing to Chopin and Schumann; I discovered a marvellous harmony between the music and their bodies made divine by the rhythm. The music inspired the dance and took it to its apotheosis. The love for dance had conquered me for life”.

The next day, he decided to return to the studio with dance shoes of his own, but Madame Nijinska categorically refused to take him on as a pupil. This dry refusal might have been motivated by the sight of his uniform. He overrode it and had himself registered as a pupil: “I worked with supreme attentiveness, but she did not seem to notice. This training lasted several months. It gave me infinite pleasure and the new joy of learning this technique, without which it is impossible for anyone to express himself”. He did this without thinking about the theatre or going on stage: “I began to discover certain notions, such as the impulses of the soul, the breath, and the physical movement of the body, which present three clearly distinct rhythms”.

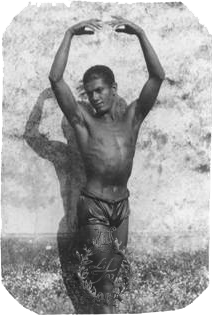

Serge Lifar when he was 16 years old

When the great ballerina set out to flee Soviet Russia for Paris, he decided to continue studying dance alone. Hermit-like, he embarked on a fifteen-month training period, spending five to six hours every day in the studio and experiencing “the joys and torments of creation, the joys and torments of work, from the loftiest ecstasy to the basest temptations”. It was during this period that he acquired his tastes in music, understanding that “rhythm is the soul of music”. He loved Mozart and Chopin more than the Russian composers, who left him cold. However, the discovery of the great poet Pushkin and the “music of his verse” came as a revelation. He devoted a cult to him throughout his life.

An adventurous escape

The temptation of expatriation began with a simple telegram sent from Paris to the Nijinska studio: “To complete his troupe, S. P. Diaghilev needs Madame Nijinska’s five best pupils”. Serge Lifar volunteered although he did not officially belong to the ballerina’s private school. His parents managed to gather enough foreign currency and cash to pay his trip as far as Warsaw. He called on the services of a smuggler to cross the border out of Soviet Russia: “Dress in such a way that you can be taken for a Red soldier. Get yourself a rifle at whatever cost”. But his flight failed miserably. Serge was thrown into prison, but managed to escape and board a freight train”.

His second attempt was successful. He bought a 3rd-class ticket in a border town for the impressive sum of 50 million roubles—runaway inflation and the printing press had done their work. He crossed the border into Poland one dark night on a sled through fields and woods, but not before having taken leave of his mother, whom he was seeing for the last time: “When it came time to say farewell, she blessed me, and I saw such fear in her eyes that I was constantly haunted by it “.

After wandering around Warsaw for weeks with two travelling companions, he finally received the money sent by Diaghilev to finance his trip to Paris: “We rushed to the stores, moved to the Bristol and were finally able to eat. In just a few hours, we looked like well-to-do provincials in their Sunday best!” The French adventure was beginning.