Serge de Diaghilev

His first steps with Diaghilev

The date of January13. 1923 marks his arrival in Paris, world capital: “I remember one of those winter mornings in which a pale sun shone through the fog; I was walking down the Champs-Elysées, enjoying for the first time the certainty of being out of danger; I was a free citizen of the universe in the freest of capitals”.

On the banks of the Seine he met the man who was to determine his destiny: Sergei Pavlovitch Diaghilev. “Among a small group of people heading toward us, I spotted a tall man who looked like a giant, walking and waving a cane, wearing a cloak and soft hat. In his rosy, slightly fat face, crowned with white locks like a Saint-Bernard, sparkled gentle brown eyes that mixed vivacity, tenderness and a sort of sadness”.

Bordeaux, 01/11/1979 : Lifar parle de sa rencontre avec Diaghilev

The small troupe travelled down to Monte-Carlo. The view of the Mediterranean, of the hills filled with flowers and olive trees made him supremely happy: “I thought that life was going to be a perpetual feast, but it took only a few hours for disillusionment to come,” he recalled in his biography. Diaghilev’s eye was merciless: “The leaps of my friends were closer to sport than to dance. When my turn came, I probably had more facility than my friends, for Diaghilev’s face brightened and a glint appeared in his eyes. He thought for a few seconds:, then said ‘alright. Let them all stay. I believe in this boy, he will be a dancer’”.

Répétition d’un ballet russe de Diaghilev

Guided by the great art critic and creator of the “Ballets Russes”, Serge Lifar was to live a new life thanks to this sure guide who would make an artist of him. Diaghilev’s few words of encouragement gave him confidence in spite of his severity: “In the eyes of the entire troupe, he was a sort of inaccessible deity, alternately benevolent and irritated. We were afraid of him. He sometimes watched the rehearsals with his retinue. He would sit, watch us dance, then express his displeasure (a word of praise from him was extremely rare), and leave”.

The Ballets Russes Company was a veritable free commune that had its own lifestyle: “Outside of rehearsals, the dancers thought only of playing, drinking and flirting with each other in the most blatant manner”.

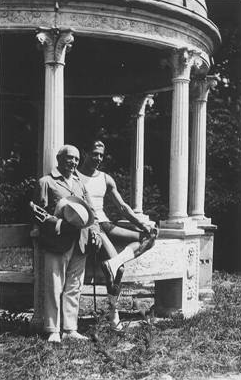

Serge Lifar et son professeur Enricco Cecchetti, 1928

The first ballet that brought him on the stage was Igor Stravinsky’s Les Noces, the rehearsals for which were directed by the great composer who sat himself at the piano and sang in a cracked voice: “Stravinsky communicated his passion to us, his creative gift, and we danced in earnest”.

Back in Paris with the entire troupe, Serge Lifar discovered the Louvre and its endless rooms, Versailles and the impressive Gallery of Mirrors. Diaghilev entrusted him with the part of the dying slave in Scheherazade, and then that of one of the officers in Les Fâcheux, on a theme of Molière. The troupe went on to Barcelona, then to Amsterdam, before returning to Paris.

There he met Picasso, who remarked to Diaghilev with a knowing eye: “The body of your little dancer has ideal proportions”. His friend Coco Chanel accompanied him throughout his life in Paris and even afterwards. Occasionally she also attended to the costumes: “He always made me laugh, something that many men have forgotten to do. When he saw that I was sad, he would come and tell me stories about his childhood in Russia, his parents. He is a real Russian, see how he drinks his tea after putting the sugar into his mouth. ”

Equipped with a train ticket to Turin and a passport arranged by Diaghilev, Lifar continued his training under Enrico Cecchetti, the “starmaker”, teacher of all the solo dancers of the Ballets Russes.

Les créatures de Prométhée Photo Henri Manuel

The great ballets: from Prometheus to Icarus

Jacques Rouché, director of the Paris Opera, a great friend and admirer of Diaghilev, suggested to Lifar that he create a ballet to the music of Beethoven’s Prometheus. He accepted, but suggested that the choreography be done by Balanchine. The latter was ill with pneumonia, so the responsibility for the choreography went to Lifar.

With Suzanne Lorcia as first dancer and Lifar’s partner, the premiere of the Creatures of Prometheus was a triumph and Rouché entrusted the Opera ballet company to Lifar from then on: “From that day on, I became a ‘maître’ and, for a quarter of a century I was greeted as ‘maître’, ‘Bonjour, maître ‘, from the little rats to the stars, I was like a happy shepherd”, he wrote in Ma Vie.

Bacchus et Ariane Photo Lipnitzki

Created in 1931, Bacchus et Ariane was an homage to Diaghilev, a completely original ballet that continued in its own way the aesthetic traditions of the Ballets Russes, with Lifar dancing the part of Bacchus and Olga Spessivtzeva that of Ariadne: “The show unleashed a storm in the audience. Some applauded loudly, while others expressed their indignation with no less force… The regulars of the Opera were not yet ready for the new aesthetics”.

The premiere of Giselle took place in February 1932, a Shakespearian drama that Olga Spesivtzeva choreographed to perfection: “In this part, she was the greatest and most sublime dancer of the 20th century. In this ballet, which I danced for 25 years all over the world, I tried to ennoble the role of Prince Albert by infusing it with an ideal, of which his death in the name of love is the symbol”. Picasso and Cocteau attended the premiere with tears in their eyes: “I, who had always struggled in my life, that night I had one of my finest triumphs”.

Ma vie, 21/10/1965 : Lifar raconte comment on l'a appelé "Maître"

Icare - Photo Pierre Boucher

Created by Nijinsky in 1912, Lifar reworked L’Après-midi d’un Faune in 1932, introducing “quick, angular movements, based on a great tension in the muscles of the entire body”.

But it was the ballet Icarus that made his reputation as a choreographer. Already in 1932, he was thinking about a ballet on this very aerial theme and began by commissioning Igor Markevitch for the score.

In the end, the ballet was created with an orchestration—or rather just rhythms—by the Swiss composer Arthur Honegger for a percussion ensemble. After being postponed several times, the premiere of Icarus was held on 9 July 1935: “I had made my wings myself and had to train my arms, because the weight upset my balance”, Lifar explained in Ma Vie.

Icare photo Lipnitzki

The sets were commissioned from Salvador Dali, but his unbridled imagination made the actual execution impossible: “Dali was delighted to collaborate with me and to work for the Opera, but unfortunately our efforts did not come through.

He showed me his sketches. To start with the sets: the curtain is raised before the music and reveals a beautiful painting, this is also raised to uncover a background curtain of the most ridiculous kind, with thirty running motorcycles.

As for the costumes: Icarus, completely naked, his head decked with a huge milk roll, and a housefly poised over the forehead on a metal wire”.1 Lifar was consoled later since he entrusted the stage curtain to his friend Picasso when the ballet was remade in 1962.

Ma vie, 21/10/1965 : L'Après-midi d'un Faune

Serge Lifar avec les clés de l’Opéra Garnier, 1940 Photo Lido/Sipa Press

Under the Occupation

As the choreographer related in his Mémoires d’Icare: “The year 1939 came and the war that had been brewing finally broke out”. The war led to the closing of the Paris Opera. Part of the troupe was sent on military or artistic missions, and even as far as Australia—a real expedition in those days. On the way back, Serge Lifar discovered Bali and Indonesian dances, which were to be a source of inspiration in the future.

Paris was occupied by German troops in June 1940, the swastika hung from the Arch of Triumph. The City of Paris asked Serge Lifar to accept the job of Director of the Opera. According to the International Hague Convention, the occupation forces had the right to confiscate any building left vacant by the State: “It is up to you to see that the Nazi flag does not fly on it for the duration of the war. You have a blank check for all your activities and it is up to you to judge how to conduct yourself vis a vis of the occupants and the personnel of the Opera in order to defend and protect this artistic heritage”. Serge Lifar became an administrator, in addition to being the concierge, floor sweeper, telephone operator, electrician, dancer, choreographer and ballet master.

“Suite en Blanc” Serge Lifar et Nina Vyroubova Photo Paul G. Almasy

Although the Nazi flag waved over Paris, the cultural life continued on the banks of the Seine. Lifar’s ballet, Suite en blanc, was performed in 1943 with a veritable constellation of stars: Lycette Darsonval, Yvette Chauviré, Micheline Bardin, Marianne Ivanoff and Paulette Dynalix. The 300th performance was held in 1961:”It is a real technical parade, a sum of the development of academic dance in the last years, a bill presented to the future by the choreographer of today “, as Serge Lifar commented in a 1954 publication that featured illustrations by such artists as Aristide Maillol, Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau.

“Giselle”, les adieux à la scène de Serge Lifar 1956

Then came time for his forced retirement

Lifar gradually entrusted the more strenuous roles to young dancers, although he still appeared on stage for gala events. It was the time to reap his rewards, the laurel wreaths that he so deserved. In 1955, he was awarded the Chausson d’or for his 25 years at the Paris Opera. The following year, he received the Gold Medal of the City of Paris. He gave courses in Choreography at the Sorbonne and was appointed professor at the Ecole Normale de Musique.

On 5 December 1956, he made his farewell to the national ballet scene by dancing Giselle with Yvette Chauviré. The twelve curtain calls went straight to his heart.

Duel entre le Marquis de Cuevas et Serge Lifar

In March 1958, he did not shrink from fighting a duel with the Marquis de Cuévas for the exclusivity of the repertoire of the Nouveau-Ballet in Monte-Carlo. The victory went to the Marquis de Cuévas, but the two men immediately reconciled. Honour had been saved. After the marquis’ death, Serge Lifar was among the casket bearers.

Ma vie, 21/10/1965 : Lifar raconte le duel avec le Marquis de Cuevas

In that same year, it came time to leave his beloved Paris Opera for good. The curtain fell on more than a hundred of his creations, a heart wrenching event. In a lecture given in Paris in December 1958, he interpreted it as a tactical measure by the French Government, “which was starting to take offence at [his] Russian origins”. He founded the University of the Dance and embarked on a new career as professor and lecturer.

Ma vie au service de la danse, 1958 : Serge Lifar s'exprime sur son départ de l'Opéra

The rediscovery of Moscow

In 1961, he was able to enjoy a reunion with his homeland behind the Iron Curtain: Moscow and the Bolshoi, Leningrad and the Kirov Theatre. He revisited Kiev, the city of his birth, which he had left 40 years before. For him, time seemed to have been abolished: “And so the trip came to a perfect conclusion. Youth was united with the wisdom to come. Kiev was reunited with Kiev. I found my house and school, my streets, and even the memory of my parents, everything except for a certain perfume of life that was gone forever. I saw the dance schools. and felt that, from then on, it was from there that the choreographic truth would come back”.